Search History

Expanded

Void Division

Collapses

SCROLL TO READ MORE

Can a penis be relieved of its supposed maleness—mere flesh in a psychic void?

Façadomy's inaugural publication, Gender Talents explores the landscape of self-determined gender. It builds off the work of progressive sexologist Esben Esther P. Benestad, who has observed seven distinct genders in their practice as a therapist in Norway. Three prominent voices in contemporary art and architecture reflect on these seven themes, intersecting gender with notions of race, sexuality and the built environment.

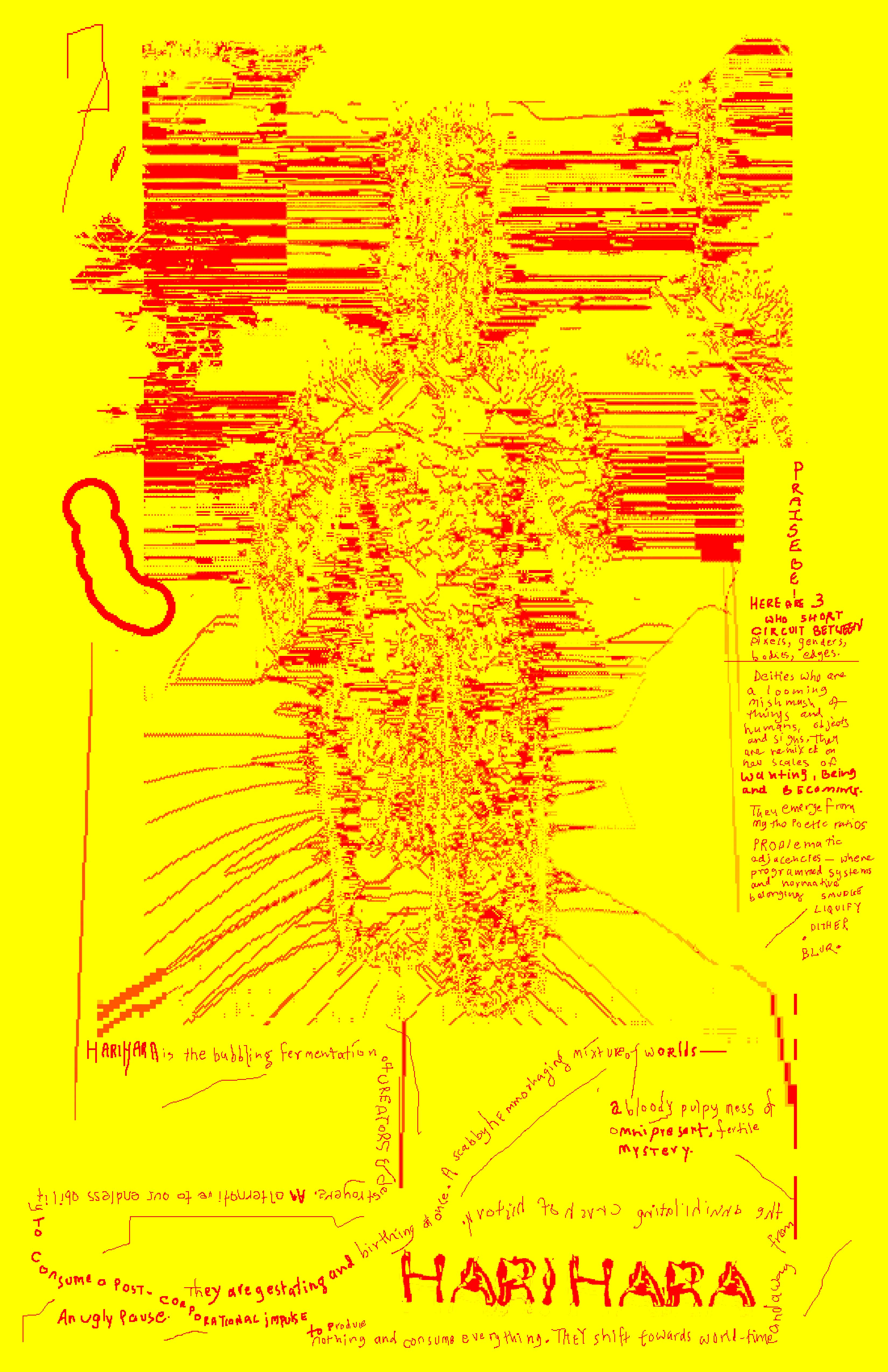

Three deities who short circuit between pixels, genders, bodies, and edges A Risograph tryptic with artist Somnath Bhatt

An artist’s signature world of grotesque, erotic and humourous domesticityArtist book with Maria Petschnig

An architectural horror/pleasure matrix with Strawberries at the center of Fidel Castro, Ice Cream, Desire and Persecution With critic Ivan L. Muñuera

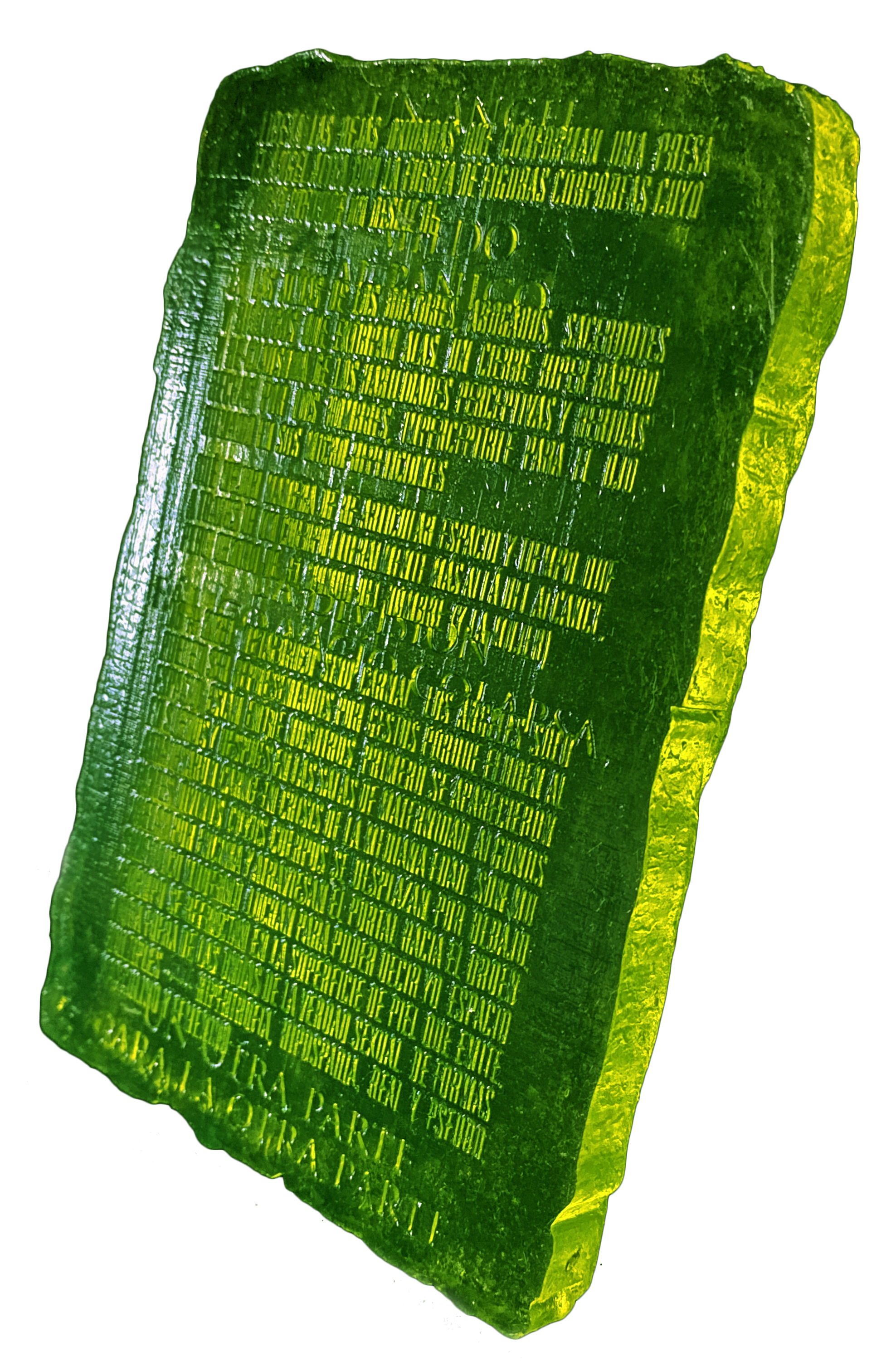

Somewhere between a clay tablet and mucal slime Resin tablet edition with Juliana Huxtable

Is that maleness innate or was it acquired and then performed? Can gender flow across somatic and cognitive planes throughout one's lifetime and forego a predetermined path altogether? Once considered radical, these are now rudimentary inquiries within the context of queer theory, but can such questions manifest into tangible realities today? How do we take steps away from essentialist assumptions about gender? Unless one has experienced such a relationship to gender within one's self, learning in this subject can only occur when appropriate language is in place. One prominent voice who constructs that vocabulary is Esben Esther P. Benestad, a sexologist and one of Norway's most public trans figures.

I first encountered Benestad in 2012, at a symposium organized by the artist Carlos Motta for his program, "We Who Feel Differently" at the New Museum in New York. I felt immediately taken by Benestad's flamboyance and unabashed reappropriation of medical diction in hir work as a sexologist and therapist in Norway. While Benestad acknowledges the human tendency toward categorization as a tenet to organizational thinking, they simultaneously resist the didacticism so often embedded in categorical frameworking. It is within this context that they have identified seven unique genders. These categories are not structured within the dominant narratives of hir field but have instead been observed through conversations with real people. Each conversation marks a movement from pre-determined to self-determined gender—a discourse of subjectivity. In Benestad's work, categorization no longer provides an overarching systemization of logic but instead serves to document an ongoing collective desire to access more nuanced terrain in regards to perceptions of gender. Furthermore, our maps of this terrain must be revised by a fundamental assumption that gender is far more fluid than our existing vocabulary can describe. In Benestad's own words:

While entirely new languages for gender have been the subject of great science fiction works, on earth in 2015, Benestad has made a practice of gradually kneading language. In most cases they favor a redefinition of the vernacular in place of inventing new words. Hir ideas are progressive in function but hir vocabulary remains familiar, expanding the lexicon of gender theory without erecting yet another barrier between those who have access to specialized rhetoric and those who do not.

The language around Benestad's work is as performative as gender itself. These seven categories—born out of individual expression—range from familiar to rare. These categories are by no means presented as definitive terms for gender. There are countless other methods of classification currently in practice and the possibility for variation is endless. What Façadomy presents here are merely alternative ways of seeing; to quote Marcel Proust, as they do in the beginning of hir lecture titled Gender Euphoria:

This first installment of Façadomy attempts just that—to navigate these categories through the eyes of another. Andreas Angelidakis presents a selection of buildings and chairs that embody Benestad's phenomena. Kimberly R. Drew pairs each gender category with a contemporary artist's work and Juliana Huxtable constructs poetic texts that imagine individuals as they channel their respective gender identities. Their perspectives are presented as a way of looking, never the way of looking. The intention is to not assert declarative, didactic assessments, but rather to use image and text to fluidly hint at a multiplicity of vantage points; to allow the buildings, objects, artworks and voices in the following pages to become part of an ever-expanding language for ever-evolving possibility.

—Riley Hooker

009

I first encountered Benestad in 2012, at a symposium organized by the artist Carlos Motta for his program, "We Who Feel Differently" at the New Museum in New York. I felt immediately taken by Benestad's flamboyance and unabashed reappropriation of medical diction in hir work as a sexologist and therapist in Norway. While Benestad acknowledges the human tendency toward categorization as a tenet to organizational thinking, they simultaneously resist the didacticism so often embedded in categorical frameworking. It is within this context that they have identified seven unique genders. These categories are not structured within the dominant narratives of hir field but have instead been observed through conversations with real people. Each conversation marks a movement from pre-determined to self-determined gender—a discourse of subjectivity. In Benestad's work, categorization no longer provides an overarching systemization of logic but instead serves to document an ongoing collective desire to access more nuanced terrain in regards to perceptions of gender. Furthermore, our maps of this terrain must be revised by a fundamental assumption that gender is far more fluid than our existing vocabulary can describe. In Benestad's own words:

I talk about "gender talents" because in that way I am opposing medicalizing terms like "syndrome," and "misshape," for example, I use the word "phenomenon." I think it is much better for a human being to be a phenomenon than to be a kind of walking disease or misfortune. In that way, I try to add to the language words that are much more positive. "talent" is a positive word. I have a very strong talent for being trans.

While entirely new languages for gender have been the subject of great science fiction works, on earth in 2015, Benestad has made a practice of gradually kneading language. In most cases they favor a redefinition of the vernacular in place of inventing new words. Hir ideas are progressive in function but hir vocabulary remains familiar, expanding the lexicon of gender theory without erecting yet another barrier between those who have access to specialized rhetoric and those who do not.

The language around Benestad's work is as performative as gender itself. These seven categories—born out of individual expression—range from familiar to rare. These categories are by no means presented as definitive terms for gender. There are countless other methods of classification currently in practice and the possibility for variation is endless. What Façadomy presents here are merely alternative ways of seeing; to quote Marcel Proust, as they do in the beginning of hir lecture titled Gender Euphoria:

The real voyage of discovery consists not of seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.

This first installment of Façadomy attempts just that—to navigate these categories through the eyes of another. Andreas Angelidakis presents a selection of buildings and chairs that embody Benestad's phenomena. Kimberly R. Drew pairs each gender category with a contemporary artist's work and Juliana Huxtable constructs poetic texts that imagine individuals as they channel their respective gender identities. Their perspectives are presented as a way of looking, never the way of looking. The intention is to not assert declarative, didactic assessments, but rather to use image and text to fluidly hint at a multiplicity of vantage points; to allow the buildings, objects, artworks and voices in the following pages to become part of an ever-expanding language for ever-evolving possibility.

—Riley Hooker

009